|

|

- Search

| Clin Exp Reprod Med > Volume 49(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a rare tumor that is more common in young people; it is an uncommon type of chondrosarcoma with a poor prognosis. In two-thirds of cases, it affects the bone, especially the spine. However, parts of the body other than the skeletal system are occasionally involved. These rarer types have a worse prognosis, with a high likelihood of metastasis and death. Due to the possible misdiagnosis of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, the integrated use of imaging, immunohistochemistry, and pathology can be helpful.

The purpose of this report is to describe the clinical and pathologic features of primary mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the ovary as an exceedingly rare entity, specifically during pregnancy [1]. Chondrosarcoma is a malignant cartilaginous tumor characterized by the formation of cartilage, but not of bone, by tumor cells and it is the third most common primary malignant bone tumor in adults [2,3].

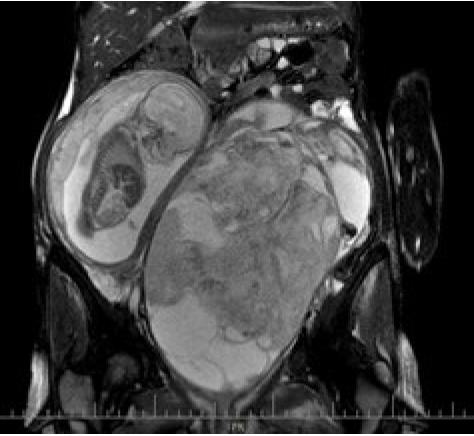

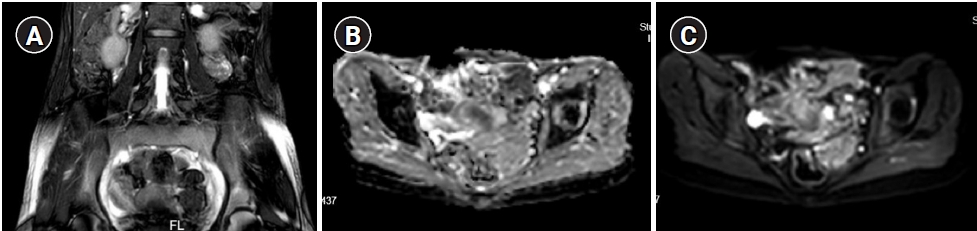

The present report describes a case of adnexal chondrosarcoma affecting a 31-year-old woman (gravida 1) at 22 weeks of pregnancy. The patient presented with chronic lower abdominal pain, was diagnosed with a 25-cm solid-cystic pelvic mass detected on ultrasonography, and was referred to our gynecologic oncology clinic. The patient was from an average Iranian middle-class family with no significant family history of gynecologic malignancy. Her pregnancy was otherwise uncomplicated, and all pregnancy screening tests were normal. The only medication at that time was pregnancy supplements. She had noticed pain in her lower abdomen over the previous month and experienced urinary retention related to the mass effect of the tumor. On a vaginal bimanual examination, a non-tender, non-mobile mass was palpable in the left adnexa that was also palpable over the abdomen and beneath the costal margin. The rest of the detailed systemic examination did not reveal any abnormalities. The patientŌĆÖs white blood cell count was 12,000/mm3 with 30% lymphocytes and 60% leukocytes. Her hemoglobin level was 6 g/dL, and she received 8 units of packed cells and fresh frozen plasma before and during surgery to maintain intraoperative hemostasis and prevent dilutional coagulopathy. The platelet count was within normal limits. Her C-reactive protein concentration was 5 mg/L. Renal function, liver function, serum electrolytes, and other biochemical investigation results were normal. A magnetic resonance imaging scan of her abdomen revealed a left adnexal mass with an internal echo (Figure 1). Since a malignancy was suspected, the patient underwent midline laparotomy and resection of the entire left adnexa and the mass. Further exploration of the resected mass revealed acute massive internal hemorrhage, estimated to be about 2,400 mL, which was the underlying cause of the patientŌĆÖs severe acute anemia. No additional abnormalities were found in the uterus and right adnexa and upon exploration of the abdominal and pelvic cavities (Figure 2). The pathological report of the mass revealed grade 3 mesenchymal chondrosarcoma with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation and without lymphovascular invasion. The mitotic rate was more than 18 per 10 high-power fields (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of cellular areas was positive for CD99 and CD34 with patchy reactivity for desmin and myogenin. CD10 was positive in areas with low cellularity. S100 and CD34 highlight chondroid islands. Smooth muscle actin, epithelial membrane antigen, Wilms' tumor protein, estrogen receptor, CD117, and cyclin D1 were negative, and the percentage of Ki-67 positivity was estimated to be 80%. Given the fact that the patient was 22 weeks pregnant by the time of surgery and the fetus was aborted spontaneously within a week after surgery, we initiated chemotherapy in agreement with the entire treatment team, including a gynecologic oncologist, fertility specialist, and radiotherapist. Postoperatively, the patient underwent 6 sessions of chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide). Three months after surgery, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging after the fifth round of chemotherapy showed a soft tissue mass measuring 112├Ś44 mm in the left adnexa with central cystic changes and an irregular and thick wall with high signal in the T1 sequence, suggesting a hemorrhagic component, and no enhancement after contrast injection. The mass shrunk in further follow-up imaging (Figure 4). The patient had no recurrence and signs of metastases as of 2 years after the last chemotherapy session.

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma was first recognized in 1959. Two years after its original description, nine cases were reported from the files of the Mayo Clinic. The first case of extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (EMC) was described in 1964. EMC accounts for about 1% of all chondrosarcomas. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma was initially considered restricted to the bone, but that is no longer the case [4]. A more recent analysis of reported cases concluded that 20% to 33% of these tumors occur in extraskeletal tissues. EMC is a rare subtype of chondrosarcoma, of chondroprogenitor cell origin [4]. The most common sites of origin of chondrosarcoma are the lower extremities, which are known as the primary sites, followed by the meninges, lung, neck, mandible, heart, and orbit. It is more common in women and mainly presents in the second to third decades of life [4,5]. Although most cases of uterine chondrosarcoma have been reported in postmenopausal women, our case was in reproductive age. In the head and neck, chondrosarcoma usually begins between the fourth and seventh decades of life. It has also been suggested that primary pure heterologous sarcomas may arise from primitive embryonal cell remnants or from a complete stromal overgrowth of a Mullerian mixed tumor. Another etiology appears to be related to the uncontrolled proliferation of Merkel cells (embryonic remains) [1,2]. Chondrosarcoma is also uncommon during pregnancy, and to the best of our knowledge no cases of proven primary ovarian chondrosarcoma in pregnancy have been reported in the literature; with regard to chondrosarcoma arising primarily in the ovary, only two cases have been reported in the English-language literature [6]. There are also some reports of primary carcinosarcomas of the uterus in the literature, although this is also a very rare condition, with 17 cases reported to date [7]. In fact, only 10 cases of gestational chondrosarcomas have been described in the literature and none of these cases affected the ovaries. The effect of pregnancy on the growth features of chondrosarcomas remains unclear. Some experts have suggested a growth-enhancing effect of altered hormone levels on various bone tumors during pregnancy [2]. In addition, it still remains unclear whether chondrosarcoma during pregnancy may show progression or dedifferentiation according to the changes in hormonal status [1]. There are reports of G1 skeletal chondrosarcoma with fast progression during the course of pregnancy in the literature. The survival rates of pregnant women with chondrosarcoma of the extremities are not likely to differ from those of non-pregnant women. However, no epidemiological data exist on the prognosis and survival rate of ovarian chondrosarcoma during pregnancy. Complications during pregnancy and delivery have only been reported for pelvic tumors; these complications include distant metastases, recurrent pain, and fetal growth restriction. As our patientŌĆÖs pregnancy was terminated spontaneously after surgery, we cannot add any data on this issue [1]. EMC has a biphasic histologic pattern comprising small cells and islands of hyaline cartilage [4]. Chondrosarcoma is divided into several subtypes, and 90% are considered as mainly slow-growing tumors with a low risk of metastases. Histologically, chondrosarcoma is graded as G1ŌĆō3, although G1 has recently been named atypical cartilaginous tumor. G3 tumors are known to have a likelihood of metastasis [1]. These tumors are diagnosed primarily based on morphology, as they have a nonspecific immune profile, and no molecular diagnostic characteristics of these tumors have been specified. On immunohistochemistry, the cartilaginous component of these tumors is strongly positive for S100 protein and the undifferentiated component is positive for CD99, as in our case. Some recent studies have discovered Sox9 as a marker that shows nuclear positivity in both undifferentiated and cartilaginous components. Other markers, including cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and muscle markers, are usually negative. However, rare cases showing scattered tumor cells with desmin, myogenin, and myoD1 positivity have also been described in tumors with areas of rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation. As described above, in our case with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, the specimen was positive for myogenin. Overall, no single best stain for this tumor has been identified, and a group of stains should be used to reach a certain diagnosis. Molecular genetic characteristics of these tumors can now be detected, including translocation (9;22) (q22; q11), resulting in the EWSR1/NR4A3 sequence in the majority of patients [5]. Wide and adequate resection of the involved area to treat localized disease is the most promising treatment option for EMC, followed by adjuvant systemic chemotherapy to treat metastatic cases. Adjuvant chemotherapy has been reported to increase the survival rate in some studies, but there is not enough evidence to reach a consensus on this matter [4,5,7]. In general, EMC is known as a highly potent tumor for distant metastasis. Most tumors are low- to intermediate-grade, although our case involved a high-grade tumor, and the clinical course tends to be prolonged in most patients. The prognosis and survival rate depend on the location of the tumor [3,4]. There is no strong evidence favoring a specific optimal option for systemic therapy. Given the aggressive nature of this tumor and poor response to treatment, some experts prefer watchful waiting in metastatic cases following wide local excision [5]. Due to the rarity of this entity, there is no established treatment protocol, and we speculated that this chemotherapy might be of benefit in this case, as the tumor was grade 3 and had a high mitotic rate. The patient had no signs of recurrence 6 months after initial wide local surgery [6]. Data on systemic treatment during pregnancy have not been reported. Despite its ethical issues, termination of pregnancy in non-obstetric chondrosarcoma may also be an option, especially during the first trimester, but it has not been recommended routinely. The absence of other valid therapy options provides the strongest arguments for a surgical approach with the maintenance of pregnancy in cases of chondrosarcomas of the extremities during pregnancy, specifically in the second and third trimesters [1]. A recent retrospective review reported a 68.2% 5-year disease-free survival rate of this malignancy [4]. In another study, the authors concluded that EMC has a relatively favorable prognosis. Some studies have detected relatively long survival times in EMC, even with metastatic disease (3┬▒5 years). A study reported greater cellularity and a higher mitotic rate with a higher likelihood of distant metastases. Nonetheless, in another two studies, the investigators found no relationship between cellularity and prognosis in EMC [3].

Our case involved a tumor with a mitotic rate greater than 18 per 10 high-power fields and grade 3 with no metastasis at the time of diagnosis. However, there are existing data on metastatic lesions observed in the liver in abdominal tomography of grade 1 chondrosarcoma [7]. The present case occurred in a pregnant woman with primary ovarian mesenchymal chondrosarcoma that was treated with surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy after spontaneous termination of pregnancy with no signs of metastasis.

Figure┬Ā1.

Magnetic resonance imaging, showing the fetus in the uterus on the right and the tumor in the left adnexa.

Figure┬Ā3.

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma pathology with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation and without lymphovascular invasion. The mitotic rate was more than 18 per 10 high-power fields. There was a biphasic mesenchymal and chondrocyte pattern. The assay was performed by immunohistochemistry technique (├Ś400).

Figure┬Ā4.

Post-chemotherapy (A) T2 axial, (B) apparent diffusion coefficient coronal, and (C) diffusion-weighted imaging coronal views on magnetic resonance imaging. An 86├Ś36-mm mass in the left adnexa with central cystic changes suggested a hemorrhagic component, with no evidence of tumor recurrence.

References

1. Roessler PP, Schmitt J, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Efe T. Chondrosarcoma of the tibial head during pregnancy: a challenging diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2014205210.

2. Cariati P, Cabello-Serrano A, Monsalve-Iglesias F, Perez-de Perceval-Tara M, Martinez-Lara I. Juxtacortical mandibular chondrosarcoma during pregnancy: a case report. J Clin Exp Dent 2017;9:e723-5.

3. Lucas DR, Fletcher CD, Adsay NV, Zalupski MM. High-grade extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a high-grade epithelioid malignancy. Histopathology 1999;35:201-8.

4. Arora K, Riddle ND. Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018;142:1421-4.

5. Elsayed AG, Al-Qawasmi L, Katz H, Lebowicz Y. Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma: long-term follow-up of a patient with metastatic disease. Cureus 2018;10:e2709.

- TOOLS