Fertility-sparing treatment in women with endometrial cancer

Article information

Abstract

Endometrial cancer (EC) in young women tends to be early-stage and low-grade; therefore, such cases have good prognoses. Fertility-sparing treatment with progestin is a potential alternative to definitive treatment (i.e., total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic washing, and/or lymphadenectomy) for selected patients. However, no evidence-based consensus or guidelines yet exist, and this topic is subject to much debate. Generally, the ideal candidates for fertility-sparing treatment have been suggested to be young women with grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma confined to the endometrium. Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed to rule out myometrial invasion and extrauterine disease before initiating fertility-sparing treatment. Although various fertility-sparing treatment methods exist, including the levonorgestrel-intrauterine system, metformin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, photodynamic therapy, and hysteroscopic resection, the most common method is high-dose oral progestin (medroxyprogesterone acetate at 500–600 mg daily or megestrol acetate at 160 mg daily). During treatment, re-evaluation of the endometrium with dilation and curettage at 3 months is recommended. Although no consensus exists regarding the ideal duration of maintenance treatment after achieving regression, it is reasonable to consider maintaining the progestin therapy until pregnancy with individualization. According to the literature, the ovarian stimulation drugs used for fertility treatments appear safe. Hysterectomy should be performed after childbearing, and hysterectomy without oophorectomy can also be considered for young women. The available evidence suggests that fertility-sparing treatment is effective and does not appear to worsen the prognosis. If an eligible patient strongly desires fertility despite the risk of recurrence, the clinician should consider fertility-sparing treatment with close follow-up.

Introduction

The most common gynecologic malignancy in developed countries is endometrial cancer (EC). Although typically diagnosed in postmenopausal individuals, 3%–14% of EC cases occur in those younger than 40 years. The overall incidence of EC has increased, most rapidly in the under 40 age group, the members of whom frequently are nulliparous and strongly desire to keep their fertility [1-5]. Because EC in young women tends to be early-stage and low-grade, a good prognosis is anticipated for such cases [6,7]. The standard treatment for EC is total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), pelvic washing, and/or lymphadenectomy [8]. Although this treatment is highly effective, it results in the permanent loss of reproductive potential, which is problematic in young patients wishing to preserve their fertility. Given both this fact and the increasing incidence of EC in younger patients, conservative management has drawn attention and has been increasingly investigated.

The core of fertility-sparing treatment is progestin therapy, as unopposed estrogen is the main cause of EC. In fact, numerous studies on various dosages of progestin and other medicines have been published [9-16]. Although it is agreed that fertility-sparing treatment can be considered for select young women with early-stage disease, the matter is complicated by the lack of evidence-based consensus or guidelines regarding target patients, treatment methods, and surveillance [17]. In this review, we will summarize data drawn from the recent literature and derive, both therefrom and from our own experience, answers to the aforementioned unresolved issues regarding fertility-sparing treatment.

Ideal target patients

Selecting ideal candidates for fertility-sparing treatment is crucial. Candidates should have a minimal risk of metastatic disease or local invasion and therefore a higher chance of regression; thus, the ideal candidates for fertility-sparing treatment have been suggested to be young women with grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma confined to the endometrium. Few studies [4,18-20] have reported the outcomes of fertility-sparing treatment for patients with more advanced disease. Park et al. [18] reported the outcomes of fertility-sparing treatment for grade 2–3 EC with or without superficial myometrial invasion. The rates of complete response (CR) to fertility-sparing treatment were 76.5%, 73.9%, and 87.5% for patients with stage IA (without myometrial invasion) grade 2–3 disease, patients with stage IA (with superficial myometrial invasion) grade 1 disease, and patients with stage IA (with superficial myometrial invasion) grade 2–3 disease, respectively [18]. Chae et al. [4] reported pregnancy outcomes of fertility-sparing treatments and demonstrated that a higher grade was also closely associated with pregnancy failure. Although a few reports have indicated that fertility-sparing treatment can be safe and effective for EC patients with grade 2–3 disease or superficial myometrial invasion [4,18-20], expansion of the criteria for target patients is not yet recommended due to the paucity of high-quality evidence.

Several groups have provided target-patient selection criteria that differ only marginally. The Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology, the European Society of Gynecological Oncology, and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology have stated that fertility-sparing treatment can be considered for women with grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma suspected of being confined to the endometrium [21-24]. The British Gynecological Cancer Society has suggested that fertility-sparing treatment may be safe in the short term for women exhibiting grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma with superficial myometrial invasion [25]. The Korean Society of Gynecologic Oncology has recommended fertility-sparing treatment for grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma limited to the endometrium if the patient strongly desires it [26]. All of these criteria account for only grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, while the criteria of these organizations regarding the degree of invasion, as alluded to above, differ only slightly. The recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

Target-patient selection criteria for fertility-sparing treatment for endometrial cancer published by different groups

Drawing together the above criteria, we believe that the proper target patients for fertility-sparing treatment are young women exhibiting grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma without myometrial invasion who strongly desire preservation of their fertility.

Appropriate pre-management evaluation

After confirmation of the histologic type of a tumor, imaging testing should be performed to rule out myometrial invasion and extrauterine disease before starting fertility-sparing treatment. Although ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used, contrast-enhanced MRI is known to be the superior method and offers the highest efficacy [27,28], especially in determining the presence of myometrial invasion. Lin et al. [29] reported that fused T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted MRI had an 88% accuracy in the assessment of myometrial invasion. CT can be a good tool for the assessment of the extrauterine encroachment of EC; however, Zerbe et al. [30] reported that the sensitivity of CT for the detection of adnexal involvement of EC was only 60%. Therefore, some authors have argued that diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed to rule out the presence of extrauterine disease before initiating fertility-sparing treatments [15]. They advocated that the occurrence of synchronous or metachronous endometrioid ovarian cancer in stage I EC limited to the endometrium in up to 25% of cases is not negligible [15,31,32]. In contrast, the Korean Gynecologic-Oncology Group (KGOG) conducted a multicenter, retrospective study that showed the incidence of synchronous ovarian cancer in women under 40 years old to be 4.5% (21/471), which is much lower than reported elsewhere [32]. Additionally, that study showed that in patients with low-risk early EC on pretreatment (no myometrial invasion, normal or benign-looking ovaries, normal CA-125, and grade 1 endometrioid histology), which generally can be considered suitable for fertility-sparing treatments, no synchronous ovarian cancer was identified at all (0/21) [33]. On that basis, the KGOG concluded that diagnostic laparoscopy is not mandatory in low-risk patients for fertility-sparing treatments [33]. To summarize, MRI is the best method available for the identification of myometrial invasion, and diagnostic laparoscopy prior to fertility-sparing treatments seems not to be mandatory.

Treatment efficacy and primary modality

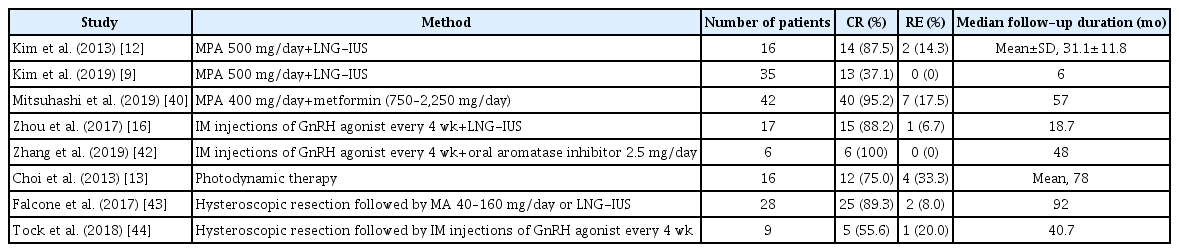

To ascertain the efficacy of fertility-sparing treatments, a meta-analysis of 32 studies was performed in 2012 and found that fertility-sparing treatment for EC was associated with a regression rate of 76.2% and a relapse rate of 40.6% [6]. However, no consensus exists regarding which agent, dose, or duration of treatment is most effective. Generally, the most commonly employed agent is medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) at 400–600 mg daily or megestrol acetate (MA) at 160–320 mg daily, as shown in Table 2. Park et al. [11] conducted a retrospective study showing that 115 of 148 patients (77.7%) achieved CR with oral MPA or MA and that MPA was associated with a lower risk of recurrence than MA (odds ratio, 0.44; 95% confidence interval, 0.22–0.88; p=0.021). Interestingly, because no patients showed clinical progression at the time of recurrence, the authors concluded that fertility-sparing treatment is safe. The response rates to MPA have varied widely by study group. According to a prospective study conducted by Ushijima et al. [34], the first of its kind, CR was achieved in 55% of women with EC who took 600 mg of MPA and low-dose aspirin orally. The outcomes of studies on fertility-sparing treatment with oral progestin [11,34-39] are summarized in Table 2. As these results were unsatisfactory, other options have been investigated. For example, the levonorgestrel-intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has been suggested, either as an alternative to or in combination with an oral agent. This system can reduce systemic adverse effects and increase local effectiveness. In a prospective trial involving the daily administration of 500 mg of oral MPA with LNG-IUS, Kim et al. [12] reported a CR rate of 87.5% (14/16 patients) and an average time to CR of 9.8±8.9 months. Subsequent to that study, the KGOG conducted a multicenter prospective investigation [9] to evaluate the efficacy of combined oral MPA/LNG-IUD treatments. However, the CR rate at 6 months was only 37.1% (13/35 patients). This lower CR rate may have been due to the short treatment and follow-up periods [9].

A few other studies have considered agents other than progestin. Metformin, as an example, can also be used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis revealed that metformin was associated with improved overall survival in EC patients [14]. Mitsuhashi et al. [40] reported that a regimen of MPA with metformin elicited a better prognosis than treatment with MPA alone with respect to relapse-free survival. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist combined with another agent also can be used. Several studies have reported the successful treatment of EC with a GnRH agonist along with an aromatase inhibitor or LNG-IUS [16,41,42]. Additionally, others have reported positive outcomes of treatment incorporating photodynamic therapy [13] and of hysteroscopic resection of the lesion combined with progestin [43] or a GnRH agonist [44]. Table 3 shows a summary of the studies on fertility-sparing treatment using various methods. However, the data on drugs other than progestin are not yet sufficient to assess their efficacy and safety for fertility-sparing treatment. In summary, given that a number of studies have established the effectiveness of systemic progestin, we recommend high-dose oral progestin (MPA 500–600 mg/day or MA 160 mg/day) as the primary choice of fertility-sparing treatment.

Method of evaluation of post-treatment response

Evaluation of the response is crucial, though no universally accepted standard protocol currently exists. Various follow-up intervals have been reported [45,46], the most frequent being 3 months [47]. Endometrial re-evaluation at 3 months can be performed with dilation and curettage (D&C), endometrial aspiration biopsy (EAB), or hysteroscopic biopsy. According to the literature [48], no significant difference in accuracy exists between D&C and EAB at the time of the initial diagnosis of EC.

However, concerns have been raised that not enough endometrial tissue is collected with EAB, due to progestin-induced endometrial atrophy at the time of re-evaluation. In fact, Kim et al. [49], based on their prospective study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of D&C with EAB in patients treated with high-dose oral progestin along with LNG-IUS, reported a diagnostic concordance of only 33% (κ=0.27). Thus, EAB might not be reliable as a follow-up evaluation method; instead, re-evaluation with D&C at 3 months is recommended over EAB.

Necessity of maintenance treatment

Regression has been reported to take 3 to 6 months to achieve with initial fertility-sparing treatments [50]. This notwithstanding, no consensus yet exists on the necessity of maintenance treatment. A meta-analysis of 29 studies reported a relapse rate for fertility-sparing treatment of 40.6% regardless of maintenance treatment [6]. According to a study by Park et al. [51], relapse rates were 31%, but patients undergoing maintenance treatment (either a combined oral contraceptive [OC] or LNG-IUS) did not experience recurrence. On that basis, they concluded that maintenance treatment with cyclic OC or LNG-IUS can be administered to prevent recurrence. Several other studies [11,34,37] have also supported maintenance treatment. For patients who do not desire to conceive, maintenance treatment with OC or LNG-IUS should be recommended to lower the risk of recurrence. Furthermore, no consensus exists regarding the duration of maintenance treatment; as shown in Table 2, several studies with various treatment durations have been conducted. Therefore, patients achieving CR should attempt to conceive immediately if possible. If patient with CR does not want to conceive soon, the clinician should decide when to stop the maintenance treatment. Recently, Chae et al. [4] reported that 49 patients who had experienced CR after treatment with 500 mg of MPA once daily tried to conceive, and 22 of those patients (44.9%) became pregnant. In that study, the maintenance treatment was stopped when two serial iterations of D&C at 3 months showed no carcinoma. The maximum duration of maintenance treatment was 49 months, and the duration of maintenance treatment was shown to have no effect on pregnancy. Although it is reasonable to consider maintaining progestin therapy until pregnancy, individualization may be required due to the lack of consensus.

Safety of fertility treatment

The safety of ovarian stimulation for EC patients remains uncertain. Clomiphene citrate is the most frequently used drug in the initial protocol for ovulation induction and may be used with gonadotropins [52]. As these drugs lead to increased estrogen production during the follicular phase, concern exists that they will increase the risk of EC [53]. Silva Idos et al. [54], reporting a large cohort study of 7,355 women among whom 43% were treated with ovulation-stimulation drugs, stated that increased EC risk may be associated with increasing cumulative dose of clomiphene citrate and, possibly, the number of cycles. Park et al. [55] examined 141 EC patients after fertility-sparing treatment. Among them, 44 patients tried to conceive with the aid of ovarian stimulation drugs, none of whom experienced recurrence and 38 of whom became pregnant. Additionally, no significant differences in 5-year disease-free survival were present between the ovarian stimulation group and the non-medication group (p=0.335). Recently, Kim et al. [56] reported that 26.3% of patients (6/22) who underwent in vitro fertilization after fertility-sparing treatments experienced recurrence over the course of a median 41-month follow-up period, and all six were then treated with hysterectomy. Particularly noteworthy was the lack of significant differences in the total duration of gonadotropin use or total gonadotropin use between patients with and without recurrence. Although that recurrence rate (26.3%) is not surprisingly high when compared with the rates of a cohort that achieved pregnancy after fertility-sparing treatment without fertility treatment, Kim et al. [56] stated that longer durations with more cautious follow-up are needed in order to avoid missing cases of recurrence. To summarize, although various opinions on the safety of ovarian stimulation drugs exist, they do appear to be safe when combined with close follow-up.

Post-childbearing necessity of hysterectomy

No controversy exists regarding the necessity of hysterectomy after childbearing is completed, because recurrence rates after CR remain high [57]. One meta-analysis reported a relapse rate of 40.6% despite maintenance treatment [6]. BSO, however, is indeed controversial. Conventionally, BSO was performed to lower the risk of recurrence for EC patients. However, many studies have reported that pre-menopausal oophorectomies were correlated with increased risk of premature death, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cognitive impairment [58-61]. Lee et al. [62] studied the impact of ovarian preservation on the recurrence and survival rates of premenopausal women with EC. Among 495 patients, 176 were in the ovarian-preservation group, and no differences in recurrence-free survival (p=0.742) or overall survival (p=0.462) were found between the ovarian-preservation group and the BSO group [62]. Similarly, another study reported that 402 women with early EC who underwent ovary-preserving treatment showed no differences in survival compared to 2,867 women with early EC who underwent BSO [63]. Although the data supporting ovarian preservation in cases of EC are limited, ovarian preservation does seem to be both safe and advantageous in cases of oocyte retrieval and surrogacy [17].

Conclusion

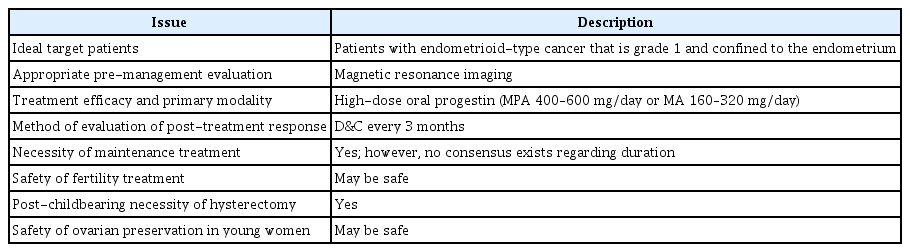

The unresolved issues regarding the fertility-sparing treatment of EC are summarized in Table 4. As emphasized above, a lack of high-quality evidence exists regarding the efficacy and safety of fertility-sparing treatments; therefore, no evidence-based consensus or guidelines have been published. The available evidence suggests that fertility-sparing treatment is effective and does not appear to worsen prognosis. If an eligible patient strongly desires fertility despite the potential risk of recurrence, the clinician should consider fertility-sparing treatment with close follow-up.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SJS. Data curation: SW. Formal analysis: all authors. Methodology & Project administration: SJS. Visualization & Writing–original draft: SW. Writing–review & editing: all authors.