Successful in vitro fertilization pregnancy and delivery after a fertility-sparing laparoscopic operation in a patient with a papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from a mature cystic teratoma

Article information

Abstract

Malignant transformation of ovarian mature cystic teratomas is rare, and papillary thyroid cancer occurs in 0.1%–0.3% of ovarian teratomas that undergo malignant transformation. We describe a case of successful in vitro fertilization pregnancy and delivery after a fertility-sparing laparoscopic operation in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from a mature cystic teratoma.

Introduction

Mature cystic teratomas (MCTs) are the most common type of ovarian germ cell tumor. Approximately 1%–2% of mature teratomas undergo malignant transformation [1,2]. The frequency of histologic detection of thyroid tissue in ovarian MCTs is less than 20% [3]. Most reported thyroid cancers in MCTs were related to struma ovarii, which contains more than 50% thyroid tissue. Struma ovarii is a type of mature teratoma constituting 2%–5% of all teratomas, and it becomes malignant in less than 5% of cases [4,5]. However, papillary thyroid cancer arising from an MCT is rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.1%–0.3% of all MCTs that undergo malignant transformation [6].

The treatment of thyroid cancer in an ovarian MCT is not well-defined because of its rarity [7-12]. Most reported patients have been treated with hysterectomy with unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (USO or BSO), fertility-preserving USO, or cystectomy, with or without total thyroidectomy [7-12]. There is no previous report of subsequent pregnancy after a fertility-preserving operation in a patient with this rare tumor. Herein, we describe a case of successful delivery after a fertility-sparing laparoscopic operation in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from an MCT.

Case report

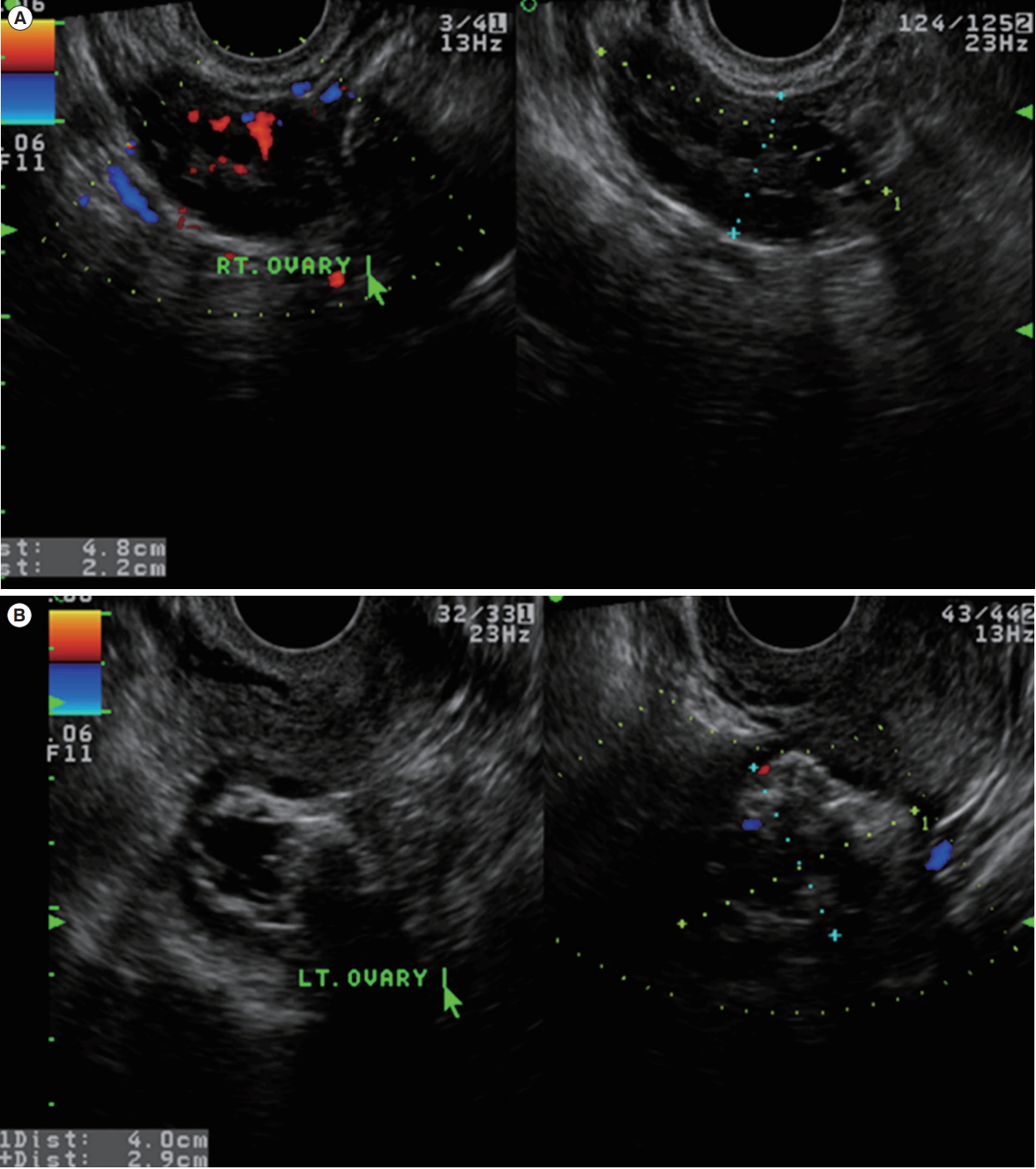

A 28-year-old, nulliparous woman was referred under the diagnosis of a left ovarian mass. Her menstrual cycle was irregular (interval, every 60–90 days; duration, 7 days), and she had experienced dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding. She had no remarkable medical, surgical, or family history. During the pelvic examination, a movable, non-tender left adnexal mass measuring about 4 cm was palpable. Pelvic ultrasonography showed a left ovarian dermoid cyst measuring 4.0×2.9 cm, and the right ovary had a polycystic appearance (Figure 1). The cancer antigen 125 level was 10.5 IU/L (normal range, 0–35 IU/L), and the serum anti-Müllerian hormone level was elevated, at >20.0 ng/mL (normal range, 0.14–12.6 ng/mL).

Preoperative transvaginal ultrasonographic findings. (A) The right (RT) ovary was normal-to-large in size with multiple small follicles. (B) The left (LT) ovary showed a mixed echoic cyst measuring 4.0 × 2.9 cm, suggestive of a dermoid cyst.

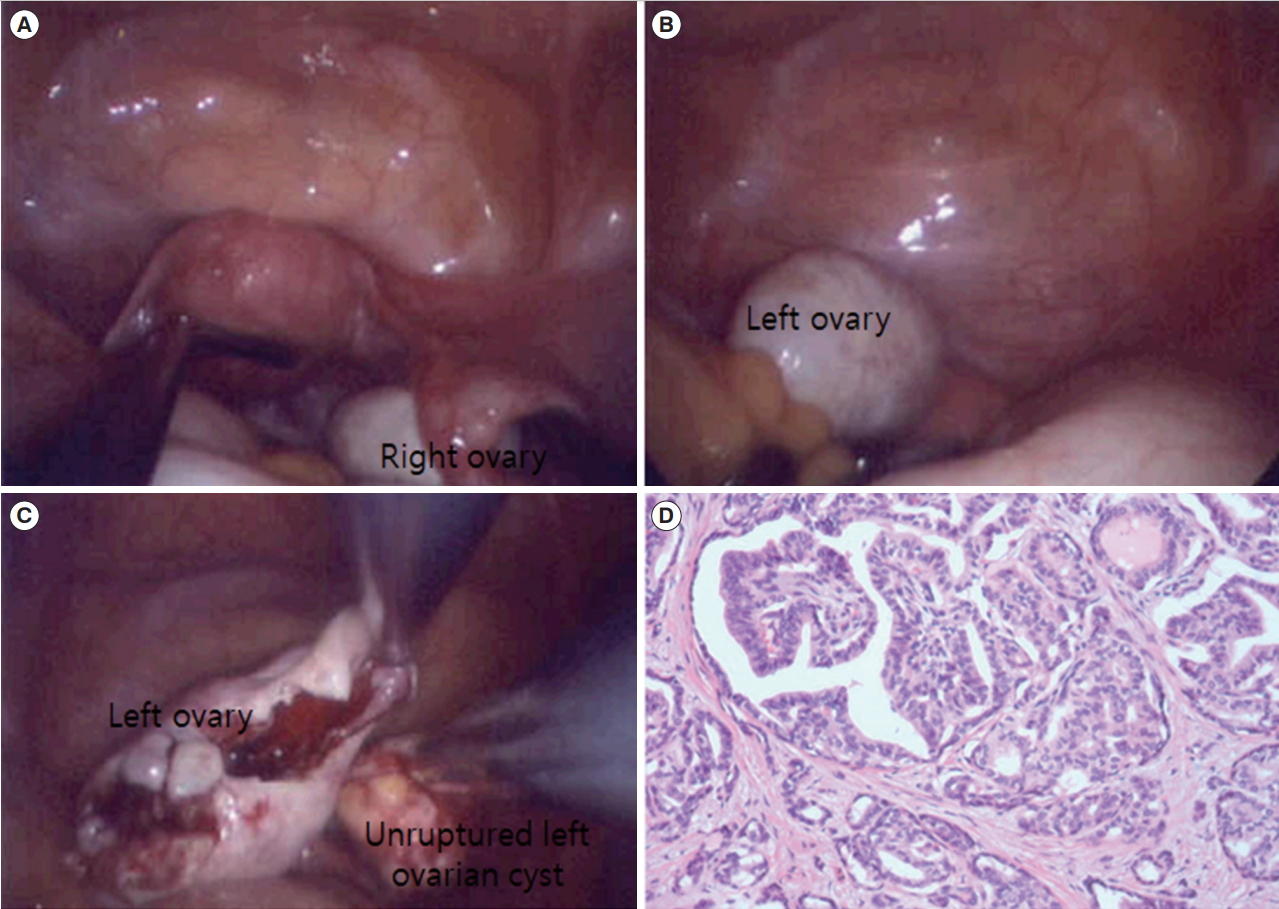

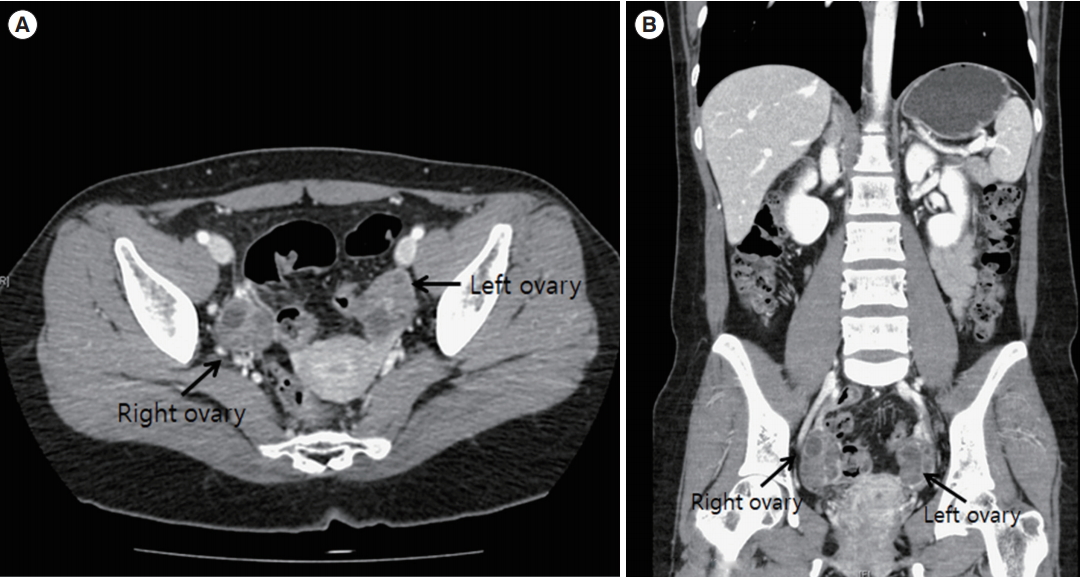

The patient underwent single-port access laparoscopic enucleation of the left ovarian cyst without spillage of the cyst content (Figure 2A-C). A diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma (measuring 0.7 cm) arising from the MCT was determined after pathologic evaluation (Figure 2D). To examine metastatic lesions in the abdominal cavity, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) was performed, and the scan was negative for metastasis (Figure 3). A sonogram of the thyroid gland showed two small, benign nodules with seven small cysts without enlargement of the thyroid glands, which indicated a benign thymus. The results of the thyroid function test (TFT) were within the normal range. Since the patient wanted to preserve her fertility, she decided to undergo fertility-preserving single-port access laparoscopic left salpingo-oophorectomy and washing cytology without thyroidectomy. The pathologic examination indicated that the tumor in the left adnexa had been completely resected. The results of washing cytology were negative for malignancy.

Initial single-port access laparoscopic findings. (A) Preoperative findings of the uterus and right ovary. (B) Preoperative findings of the left ovary. (C) After enucleation of the left ovarian cyst, there was no spillage of the left ovarian cyst content. (D) Papillary thyroid carcinoma arising in a mature cystic teratoma (H&E, × 200). Multiple papillae and follicles are shown, lined by tumor cells with optically clear nuclei and irregular nuclear membranes.

Postoperative computed tomography scan findings. (A) On the axial view, both ovaries were prominent, without a definite focal lesion. (B) On the coronal view, there was no evidence of distant metastasis or significant lymph node involvement in the abdomen and pelvis.

Six months later, a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan showed no evidence of strong focal fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake that would suggest a malignant lesion or metastasis; there was only mild heterogeneous FDG uptake in the right ovary and uterine cavity, which was considered to reflect physiologic uptake. The tumor markers and results of TFT were also within the normal limits. The presumed stage was International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage Ia. Therefore, further postoperative adjuvant treatment was not necessary.

Since the patient’s menstrual cycle was still irregular due to known polycystic ovarian syndrome, she was referred to our fertility center to undergo assisted reproductive technology. After clomiphene citrate with timed coitus failed twice, she underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF). In her first IVF cycle, recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (Follitrope 150 IU; LG Chemical, Seoul, Korea) with a starting dose of 150 IU was injected on menstrual cycle day (MCD) #3, and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (Cetrotide; Merck Serono, Darmstadt, Germany) was added on MCD #8. On MCD #10, when the leading follicles reached 19 mm in diameter, ovulation was triggered by an injection of 250 μg of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (Ovidrel; Merck Serono). The oocytes were retrieved 36 hours later. In total, 27 oocytes were retrieved and 12 were discarded. After ovum pick-up, the patient experienced moderate ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; therefore, embryo transfer was postponed, and all embryos were frozen (four morulae and 10 blastocysts were frozen, while one embryo at the cleavage stage was discarded). In the next menstrual cycle, two blastocysts were hatched, thawing embryo transfer was performed, and she successfully conceived dichorionic diamniotic twins. Her delivery was successful through a cesarean section at 37 weeks of gestation. She was followed up for 59 months after the fertility-preserving laparoscopic operation and had no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

Teratomas are derived from all three embryonic germ layers: ectodermal tissue (skin, hair, and sebaceous glands), mesodermal tissue (bone, cartilage, muscle, heart, lymph cells, and spleen), and endodermal tissue (digestive tract, pancreas, liver, and thyroid); all of these constituents have the potential to undergo malignant transformation within a tumor [1,2,6]. Additionally, most patients with malignant transformation of a teratoma are incidentally diagnosed postoperatively during pathologic review.

As the number of reported patients with a thyroid carcinoma arising from an ovarian MCT is very limited, treatment modalities are not well-described. Most reported cases of thyroid cancers in MCT are related to struma ovarii. Diverse treatment strategies have been reported, ranging from conservative surgery with the goal of preserving fertility to radical surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy with or without thyroidectomy [7-15]. Malignant struma ovarii commonly arises in the fifth decade of life; therefore, the mainstream treatment modality is hysterectomy with BSO [7-15]. Thyroidectomy, radioiodine treatment, and suppressive thyroid-stimulating hormone treatment are recommended as adjuvant therapy of struma ovarii [4,7-12,15]. However, adjuvant therapy remains controversial [7-15].

Similar to other ovarian tumors, teratomas can spread directly to other regions, such as the peritoneal cavity, omentum, and opposite ovary, as well as distant sites. However, with papillary thyroid carcinoma, metastasis to the regional and paraaortic lymph nodes is expected [15]. Devaney et al. [14] reported the prognosis of 13 patients with malignant struma ovarii; 11 patients had papillary carcinomas, two had follicular carcinoma, and no patients underwent additional treatment postoperatively. No recurrence was reported during the 7-year follow-up period. Some authors have suggested 131I treatment when a patient’s serum thyroglobulin level is >10 ng/mL, because 98% of patients with thyroid cancer with a serum thyroglobulin level <10 ng/mL are free of disease [15].

If residual malignant disease or distant metastases exist postoperatively, total thyroidectomy and radioablation with 131I is possible [8-10]. In patients with recurrent or metastatic disease, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and thyroid suppression are possible treatments [7-12]. In patients with no invasion or metastasis, the prognosis of malignant struma ovarii is good [12]. Since our patient had never conceived a child, we decided to perform a fertility-preserving operation. According to a case series, papillary thyroid carcinoma of thyroid tissue in an ovarian teratoma (excluding struma ovarii) had not been reported until 2012 [10]. In that review, only seven patients who underwent conservative treatment, such as tumor resection or USO, were selected, and there were no patients with a subsequent pregnancy [10]. Recently, Iwahashi et al. [16] reported a case of live birth after fertility-sparing surgery of papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from a MCT. In their case report, a 30-year-old multiparous woman conceived her second child naturally and delivered 2 years after fertility-sparing surgery. There was no evidence of recurrence in 6 years of postoperative follow-up. Unlike the reported case, our case is the first report of successful delivery after a fertility-sparing laparoscopic operation using IVF in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from an MCT.

In the earlier literature, hypotheses were proposed regarding the origin of epithelial ovarian cancer (not in germ cell tumors). According to the incessant ovulation hypothesis, ovulation itself causes recurrent minor trauma of ovarian epithelial cells. During the repair process, aberrant repair leads to malignant transformation [17]. In gonadotropin hypothesis suggests that high levels of circulating gonadotropins produce high levels of estrogen or estrogen precursors and stimulate ovarian surface epithelial entrapment in inclusion cysts, and proposes that proliferation of these inclusion cysts with dysplasia can cause malignant transformation [18]. Therefore, concerns were raised regarding the possible ovarian cancer risk associated with the use of ovarian stimulating drugs for infertility. Rizzuto et al. [19] reviewed 182,972 patients in 11 case-control studies and 14 cohort studies, and found no convincing evidence of an increase in the risk of invasive ovarian cancer during fertility drug treatment, although an increased risk of borderline ovarian tumors was observed. In our case, during the first surgical procedure, there was no spillage of cyst content, and in the subsequent fertility-sparing operation, there was no residual tumor. Six months after fertility-sparing surgery, there was no evidence of residual or recurrent disease on PETCT. The patient tried to conceive in a relatively short interval of 6 months after fertility-sparing surgery, starting with two cycles of clomiphene citrate with timed coitus, and in her first IVF trial, she became pregnant and successfully delivered healthy twins. Fertilitysparing operations are desirable for women who have a low-grade disease and wish to conceive. However, a future study with a longer follow-up is needed to evaluate the safety of this conservative treatment, the most appropriate interval of the pregnancy trial (including IVF procedures), and the safety of ovarian-stimulating drugs in terms of ovarian cancer risk.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MLK, BSY. Software: AKWH, KH, BSY. Data curation: KH, JYS. Formal analysis: MLK, SJS. Methodology: MLK. Investigation: HSJ, SJS. Supervision: MLK, BSY, SJS. Writing - original draft: KH. Writing - review & editing: MLK, BSY, HSJ, SJS.