|

|

- Search

| Clin Exp Reprod Med > Epub ahead of print |

Abstract

Objective

Cisplatin (CP) is a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, but its severe side effects impact testicular function. We investigated the potential protective effects of bilberry extract against CP-induced testicular toxicity.

Methods

Forty adult male albino rats were divided into four groups. Control animals received a single oral dose of 0.9% saline. Bilberry-treated rats received oral bilberry extract (200 mg/kg body weight [BW] dissolved in 1 mL of saline) daily for 10 consecutive days. CP-treated animals were administered a single intraperitoneal dose (7.5 mg/kg BW). Finally, a bilberry+CP group received oral bilberry extract (200 mg/kg BW) daily for 10 consecutive days, with one intraperitoneal dose of CP (7.5 mg/kg BW) on day 2. We assessed sperm count, motility, viability, and abnormalities, along with testis weight, testis weight-to-BW ratio, antioxidant activity, levels of oxidative stress markers (malondialdehyde [MDA] and hydrogen peroxide [H2O2]), sex hormones (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], luteinizing hormone [LH], and testosterone), and apoptotic and anti-apoptotic markers, and DNA damage. Testicular tissue underwent histopathological examination.

Results

Among CP-treated rats, significantly lower values were observed for testis weight; testis weight-to-BW ratio; levels of FSH, LH, testosterone, superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione S-transferase, glutathione, and B-cell lymphoma 2; and sperm count, motility, and proportion of normal sperm. CP administration was associated with higher MDA, H2O2, p53, Bax, cytochrome c, caspase 9, and caspase 3 levels, along with elevated tail moment. However, bilberry extract administration significantly improved all altered parameters.

Cisplatin (CP; cis-diammine-dichloro-platinum) is a platinum-based anticancer drug utilized in the treatment of various solid tumors, such as those of the ovary, breast, colon, testes, and uterine cervix [1]. The antineoplastic activity of CP is mediated through the induction of apoptosis and the formation of DNA crosslinks, which exert cytotoxic effects on malignant cells [2]. However, the clinical application of CP is limited due to its severe adverse effects. Notably, CP is associated with over 40 side effects, including damage to the heart, liver, testes, kidneys, and reproductive system [3].

The exact mechanism by which CP toxicity affects the testes has not been fully elucidated. Consequently, several hypotheses have been put forward to explain CP-induced toxicity, the most notable of which is oxidative stress [4]. Research has indicated that CP toxicity in tissues is associated with increases in malondialdehyde (MDA), a byproduct of polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [5]. Additionally, CP has been found to reduce the activity of antioxidants like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH), and glutathione S-transferase (GST), which represent a defense system against free radical damage [6,7]. Oxidative stress can lead to alterations in protein synthesis and inhibit DNA transcription and replication [8]. Another proposed mechanism of CP-induced toxicity in the testes is its ability to induce apoptosis in germ cells [9]. CP not only damages testicular tissue, including Leydig and Sertoli cells, but also disrupts the production of sex hormones. This results in a decrease in testosterone levels, which in turn affects the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), leading to alterations in spermatogenesis [10].

Substantial research has indicated that antioxidants can mitigate the toxic effects associated with CP administration [11]. Antioxidants are crucial in reducing oxidative stress and shielding cells from damage caused by free radicals [12]. Additionally, research has shown that natural products can offer protection against diseases related to oxidative stress [13].

Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), commonly known as the European blueberry, is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Ericaceae family, predominantly found in Europe and North America. It is abundant in antioxidants, including anthocyanins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and their derivatives [14]. Furthermore, bilberry has been shown to possess a range of beneficial properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, antilipemic, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, and retinoprotective effects [15,16]. Multiple studies have examined the protective role of bilberry against the toxicity induced by various chemotherapeutic agents [17,18]. Consequently, the objective of this study was to explore the potential protective effects of bilberry against CP-induced testicular toxicity in rats.

Forty male albino rats, each weighing approximately 210 g, were acquired from the Agricultural Research Center in Giza, Egypt. These rats were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with the room temperature set at 23 ┬░C and the humidity at 60%. Prior to the start of the experiment, all rats underwent a 1-week acclimatization period to ensure their well-being. Throughout the study, the animals had access to a standard diet and water ad libitum.

The chemicals utilized in this study met the standards for molecular biology and diagnostic applications. Sigma-Aldrich supplied these reagents. We acquired bilberry powder, which was weighed at 500 mg (GNC), from a source in Saudi Arabia. CP was procured from Hospira, a subsidiary of Pfizer.

The rats were randomly allocated into four groups, with each group comprising 10 animals. The control group was given a single oral dose of 0.9% saline. Rats in the bilberry group received an oral administration of bilberry extract, at a dosage of 200 mg/kg body weight (BW) dissolved in 1 mL of saline, daily for a duration of 10 days. The CP group was treated with a single intraperitoneal injection of CP at a dose of 7.5 mg/kg BW [6]. Lastly, the bilberry+CP group was administered 200 mg/kg BW of bilberry orally via a stomach tube for 10 consecutive days, with an intraperitoneal injection of 7.5 mg/kg BW of CP administered on the second day [18].

Upon completion of the experiment, the animals from each group were euthanized with an intraperitoneal overdose of thiopental at a dosage of 10 mg/kg. Blood samples were collected and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3,000 rpm, after which the resulting sera were transferred into clean Eppendorf tubes for subsequent biochemical analyses.

Epididymal sperm analysis was conducted in accordance with the methodology outlined by Seed et al. [19]. Seminal fluid was examined using an optical compound microscope to assess sperm count and motility. Subsequently, sperm were stained with eosin as described by Ciftci et al. [20]. The total sperm count per gram of tissue was determined, and the proportion of motile sperm from the caudal epididymis was quantified using phase-contrast microscopy. Specifically, sperm were categorized as either motile or immotile. To evaluate the morphological abnormalities of the spermatozoa, slides stained with eosin-nigrosin were prepared. The sperm were then analyzed based on the morphologies of their heads and tails, and the rates of spermatozoa with anomalies were calculated.

The levels of H2O2 and GST were determined using a colorimetric method with a kit acquired from Bio Diagnostic, and measurements were taken spectrophotometrically using a Uvikon 930 device (Kontron Instruments). The level of MDA in red blood cells was measured according to the method described by Stocks and Dormandy [21], which involves the use of thiobarbituric acid to produce a colored complex for colorimetric assessment. GSH levels were estimated following the protocol of Beutler et al. [22]. This method includes the use of metaphosphoric acid to precipitate proteins and the application of water-soluble 5,5'-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid to develop color. CAT activity was assessed using the technique detailed by Chance and Maehly [23], wherein CAT reacts with a predetermined quantity of H2O2. After exactly 1 minute, the reaction is halted with a CAT inhibitor. SOD activity was measured based on the method of DeChatelet et al. [24], which relies on the enzymeŌĆÖs capacity to inhibit the phenazine methosulfate-mediated reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium dye. Blood levels of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), Bax, P53, and caspase 9 were quantified using kits from MyBioSource, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedures were performed with a Stat Fax 4700 apparatus (Awareness Technology Inc.). Concentrations of caspase 3 and cytochrome c in the blood were determined with kits from CUSABIO. Serum testosterone levels were measured using a kit from Abcam. Finally, serum FSH and LH concentrations were quantified with a kit obtained from MyBioSource. The apparatus utilized for measuring chemical reactions and colorimetric methods was produced by Robonik.

Single-cell gel electrophoresis, also known as the Comet assay, was conducted in accordance with the protocol described by Bajpayee et al. [25]. This assay involves the detection of DNA strand breaks within single cells from seminal fluid, which are immobilized on a microscope slide. Typically, between 50 and 100 cells are randomly selected from each sample and analyzed for tail length, the proportion of tail DNA, and the tail moment.

The left testis of the rats from all groups was removed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in a series of increasingly concentrated buffered ethanol solutions, cleared in xylene, and subsequently embedded in paraffin wax. Tissue blocks thus prepared were sectioned to a thickness of 5 ╬╝m. These paraffin-embedded sections were then mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and subsequently examined and photographed to identify any pathological alterations within each testis, following the methodology described by Bancroft and Gamble [26].

Results were presented as mean (n=10)┬▒standard error. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance [27]. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc.). Differences were considered significant when indicated by p-values of 0.05 or less.

All biological experiments were conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences. The research was conducted at Mansoura University, located in Mansoura, Egypt. The Institutional Review Board of Mansoura University, Egypt, granted ethical approval for this study, with the approval number MU-ACUC (SC.MS.22.09.3).

Significant reductions were observed in both testis weight and testis weight-to-BW ratio in the CP animals relative to the control rats. The group treated with bilberry exhibited significant recovery in these measures relative to the CP group; however, the values did not reach the levels observed in the control animals (Table 1).

Treatment with bilberry resulted in significant improvements compared to treatment with CP injection alone. CP was found to induce oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation by significantly increasing markers of oxidative stress, such as MDA and H2O2. This was accompanied by significant decreases in the activities of antioxidants, including SOD, GST, and CAT, as well as a reduction in GSH content (Table 2).

CP was observed to induce alterations in spermatogenesis, resulting in significant reductions in sperm count, motility, and viability. In contrast, the rats treated with both bilberry and CP exhibited a significant ameliorative effect compared with the animals administered CP alone (Table 3).

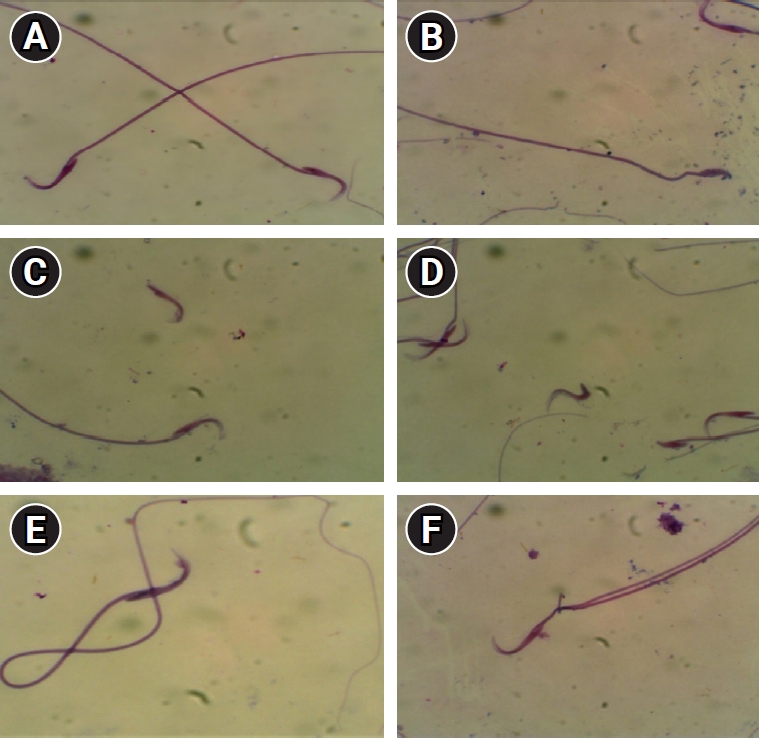

Alterations in sperm morphology induced by CP resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of abnormal sperm alongside a significant decrease in the percentage of normal sperm. The group treated with bilberry+CP exhibited significantly better parameters, as demonstrated in Table 3, Figure 1.

Alterations in gonadal hormones induced by CP involved significant reductions in FSH, LH, and testosterone levels compared to the control group. These levels were significantly ameliorated in the bilberry+CP group compared to the CP animals; however, the hormonal concentrations did not reach the values observed in the control group. Bilberry administration alone yielded normal hormonal levels, similar to those in the control group (Table 4).

The administration of CP was associated with significant increases in apoptotic markersŌĆöp53, Bax, cytochrome c, caspase 3, and caspase 9ŌĆöand a significant decrease in the anti-apoptotic marker Bcl-2 relative to the control group. In comparison, the group treated with bilberry+CP exhibited significantly higher Bcl-2 levels and lower apoptotic activity (Table 5).

The CP-induced DNA damage, as shown via single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet assay), was characterized by significant increases in tail moment, length, and DNA content. However, pretreatment with bilberry was associated with a significant rise in tail moment, but did not demonstrate a significant increase in either tail length or tail DNA, as shown in Table 6, Figure 2.

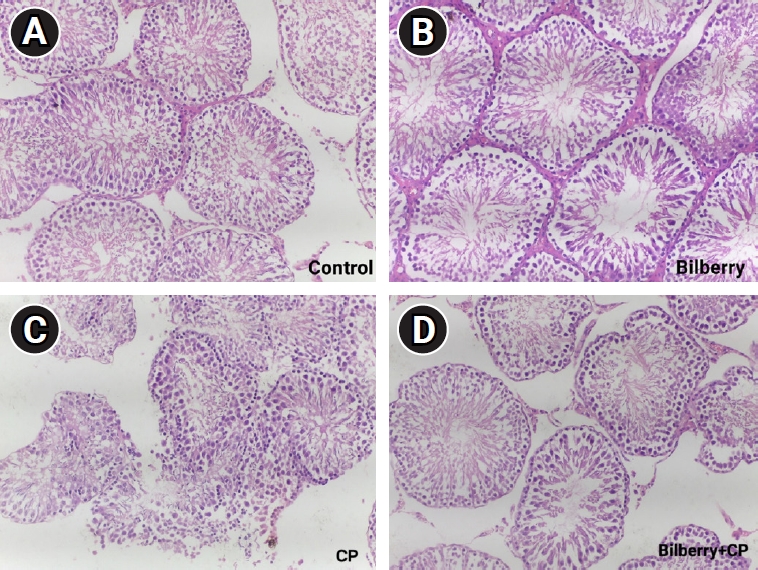

Figure 3 depicts the histological examination of testicular tissues from the four groups, with slides observed under ├Ś200 magnification. Morphologically, the seminiferous tubules, spermatogenic stages, Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and interstitial spaces exhibited normal patterns in both the control and bilberry groups. In contrast, the CP group displayed abnormalities in the stages of spermatogenesis and testicular morphology. However, the bilberry+CP group demonstrated mild improvement in the normal organization of spermatogenic cells and spermatogenic process.

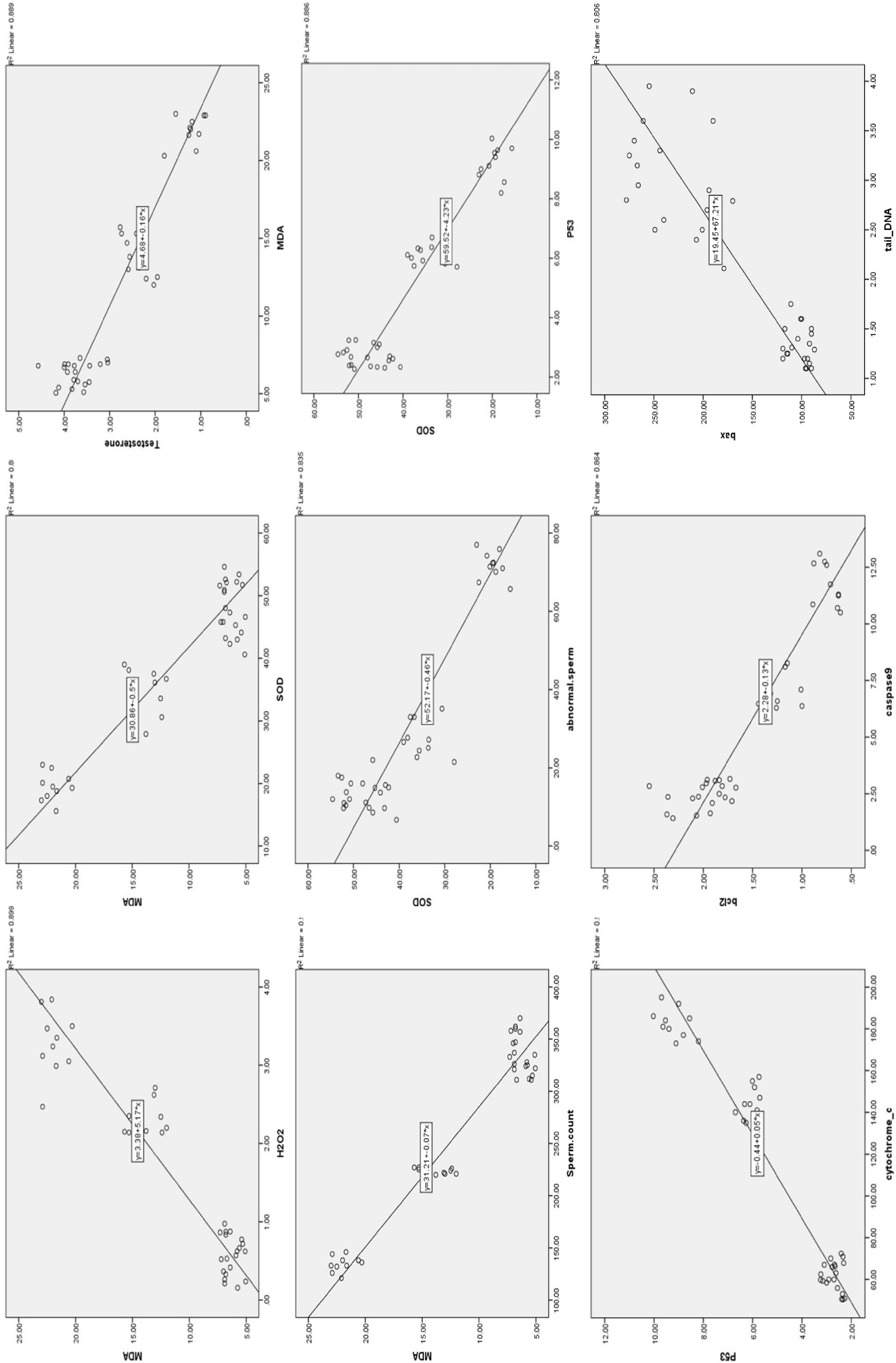

Correlations among the various parameters investigated are depicted in Figure 4. In this study, exceptionally strong positive correlations were observed among all antioxidant parameters. Moreover, highly significant negative correlations were found between the concentrations of antioxidants examined in this study and levels of oxidative stress markers, namely MDA and H2O2. Highly significant negative correlations were observed between fertility hormone levels and markers of oxidative stress. Conversely, highly significant positive correlations were identified between antioxidant and fertility hormone levels, although these data are not presented here. Strong positive correlations were observed between markers of apoptosis and oxidative stress, as well as between apoptosis markers and DNA moment. Conversely, strong negative correlations were identified between antioxidant levels and both apoptosis and DNA moment. Strong negative correlations were observed between testicular weight and markers of oxidative stress, as well as between oxidative markers and sperm count, the proportion of sperm with normal morphology, and sperm motility. We found that there is negative correlation between oxidative stress and sperm motility, with increasing the oxidative stress markers the sperm motility decreases. The same for the correlation between sperm concentration and oxidative stress markers. The same for the correlation between sperm morphology and oxidative stress markers. Conversely, strong positive correlations were identified between levels of antioxidants and testicular weight, in addition to sperm count, normal sperm morphology, and motility.

As previously indicated, strong positive correlations were observed between markers of apoptosis and oxidative stress. Conversely, strong negative correlations were identified between antioxidant levels and apoptosis. Additionally, strong negative correlations were found between apoptosis and normal sperm morphology, as well as between apoptosis and both sperm count and motility.

The growing prevalence of cancer, now a leading contributor to global morbidity and mortality [28], has led to the widespread use of antitumor drugs such as CP. The generation of ROS induces oxidative damage and causes adverse side effects upon CP administration, with dose-dependent severity [29]. CP inflicts damage on the testes by causing germ cell death, Leydig cell dysfunction, and disruption of testicular steroidogenesis, ultimately leading to infertility [9,30]. Consequently, the use of a potent antioxidant has been suggested as a prophylactic strategy to mitigate CP-induced testicular toxicity in male patients.

Bilberry is rich in antioxidants, particularly anthocyanins, which constitute the largest portion of the fruitŌĆÖs phytochemical content. Typically, the concentration of anthocyanins in bilberries ranges from 300 to 700 mg per 100 g of fresh fruit. In addition to anthocyanins, bilberries contain substantial amounts of other antioxidants, including vitamin C, flavanols, and phenolic acids [31,32]. Research has primarily focused on anthocyanins due to their abundance in bilberries and their potent antioxidant properties. These properties are implicated in various biological processes, such as cell signaling pathways, DNA repair, cell adhesion, and gene expression, and they also exhibit antineoplastic and antimicrobial effects [33].

The present study revealed increased levels of oxidative markers, including MDA and H2O2, alongside decreased levels of antioxidant markers such as GST, SOD, CAT, and GSH. These findings align with previous research, which has indicated that CP-induced alterations in oxidative stress status stem from an overproduction of ROS. In the present study, this overproduction impaired the antioxidant defense systems in the testes of the CP group relative to the control group [18,34-37]. Additionally, CP administration was found to cause significant decreases in both enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, GST, CAT) and the non-enzymatic antioxidant GSH, which is depleted as it scavenges the free radicals released by CP administration. These observations are consistent with those of a separate study [38], which attributed the changes to uncontrolled generation of H2O2, further impairing the testicular antioxidant defenses.

Furthermore, the present results align with prior research demonstrating a significant increase in DNA damage. Growing evidence suggests that oxidative stress, induced by ROS generation in testicular cells, plays a key role. These cells are considered a primary target due to their high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, active protein synthesis, and processes of spermatogenesis and DNA packaging [39]. The CP-induced overproduction of toxic byproducts, such as MDA, causes damage to membrane proteins. This damage can inactivate receptors and membrane-bound enzymes, which may result in cross-linking and polymerization of membrane components. Such changes can obstruct DNA transcription and replication, altering associated proteins and triggering either repair mechanisms or normal cell apoptosis. This is one potential explanation for the observed sperm abnormalities [40-43]. Our study corroborates these findings by reporting a positive correlation between oxidative stress (as indicated by MDA levels) and DNA damage. Negative correlations were also observed between testicular function and oxidative stress, which is consistent with previous research [44].

The present data align with findings from a study indicating that lipid peroxidation promotes disruption of the lipid matrix structure within the spermatozoa membrane. This results in weakened protective mechanisms and a reduction in sperm motility [45]. This decline in sperm motility is linked to an excess production of oxidative stress, a decrease in antioxidant activity, and a reduction in adenosine triphosphate, which is crucial for the movement of the spermŌĆÖs flagellum [46]. These observations are in line with the negative correlation between oxidative stress and sperm motility reported in this study.

Bilberry is abundant in antioxidants, which directly counteract the increased oxidative stress induced by CP administration [32]. These compounds scavenge free radicals and influence a range of biological and enzymatic reactions.

In the present study, treatment with bilberry was associated with lower H2O2 and MDA levels compared to the CP group. Relative to the same group, bilberry treatment promoted higher activities of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, CAT, and GST, and an increase in the non-enzymatic antioxidant GSH. These findings are consistent with numerous previous studies [18,47,48], which suggest that bilberry can form stable radicals with ROS by donating hydrogen ions and altering cell signaling pathways. Since antioxidant activity can be compromised by high levels of oxidative stress, bilberry appears to bolster antioxidant defenses by diminishing the presence of toxic markers.

The histopathological findings of the present study align with recent data [49,50]. CP induces oxidative stress, leading to structural damage in biological macromolecules and cellular components, including nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. This damage affects not only cancer cells but also normal and stem cells [6]. It also results in testicular injury and structural abnormalities in the testes, as evidenced by the observed histopathological alterations. These include marked parenchymal atrophy, in addition to severe changes such as testicular fibrosis, necrosis, a reduction in the number of seminiferous tubules, decreased germinal cell layer thickness, impaired maturation of germinal cells, and arrested spermatocytes at various stages of division, all of which contribute to tubular shrinkage in testicular tissues [46,51]. Additionally, considerable degeneration and damage occur to the germinal epithelium and spermatogenesis, which appear to be associated with oxidative stress and apoptosis [46]. Other studies have attributed these effects to the accumulation of H2O2, which disrupts the antioxidant defense system, findings that are consistent with our study [52]. Specifically, this would explain the positive correlations observed between oxidative stress and both apoptosis and testicular damage. In the present study, bilberry treatment alone did not induce any histopathological changes in testicular tissue when compared to the control group. However, oral administration of bilberry prior to and concurrently with CP treatment had a protective effect due to its ability to modulate antioxidant activity and reduce the oxidative stress caused by CP.

The findings of the present study are consistent with other reports indicating that CP leads to a decrease in testicular weight [9,53]. The observed reduction in testicular weight within the CP group can be attributed to various histological alterations, such as the atrophy of the parenchymal tissue and a decrease in the thickness of the germinal cell layer [45]. Testicular weight is contingent upon the mass of differentiated spermatogenic cells, and maintaining its structural and functional integrity necessitates the adequate biosynthesis of male sex hormones. Consequently, a reduction in testicular weight in CP-treated rats indicates impaired spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis [54], a finding corroborated by the histopathological results of our study. Furthermore, the effect of CP on histopathology is confirmed by the study of Eid et al. [53]. However, the outcomes of the current investigation do not align with those reported by Dare et al. [37].

Our findings corroborate the results of a recent study suggesting that a decrease in BW may be linked to diminished food intake and metabolic dysfunction, which are frequently observed symptoms following CP administration. These associations are also supported by earlier research [55].

All previously described factors contributed to reductions in sperm concentration, viability, normal morphology, and motility, as well as an increase in sperm morphological abnormalities, relative to the control group. These results are consistent with findings from earlier studies [56,57]. Moreover, bilberry supplementation has demonstrated a protective effect on testis weight and the testis weight-to-BW ratio. This protective effect may be attributed to the capacity of bilberry to mitigate oxidative damage induced by CP and to neutralize ROS, thereby diminishing the damage caused by CP [58]. Through its potent protective properties and rich antioxidant content, bilberry reduces DNA, protein, and lipid damage resulting from oxidative stress. Consequently, it counteracts the effects of CPŌĆöas evidenced by improvements in semen analysis and fertility hormone levelsŌĆöby providing membrane protection [59,60].

The observed reduction in fertility hormones such as testosterone, FSH, and LH following CP exposure aligns with findings reported in the literature [52,61]. This reduction may be attributed to the extensive damage inflicted by CP on Leydig and Sertoli cells, particularly Leydig cells, which are responsible for testosterone secretion [46,62]. An alternative hypothesis suggests that the effects of CP could stem from its interference with LH receptor expression, disruption of cholesterol mobilization to mitochondrial cytochrome P450, or inhibition of the activity of this enzyme, all of which could impede the initial stages of testosterone synthesis. LH normally stimulates Leydig cells to produce testosterone [46]. Testosterone depletion prompts an increased release of LH, which binds to Leydig cell receptors to boost testosterone production, a compensatory response within the negative feedback mechanism of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis [63]. However, CP damages the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis [10], leading to declines in FSH, LH, and testosterone levels. The reduced testosterone levels may also be linked to a decrease in the number of LH receptors on Leydig cells [51]. In this study, the diminished LH levels in rats treated with CP indicate hypopituitarism and a reduced responsiveness of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis to the feedback regulation by testosterone and LH. Thus, a negative correlation exists between oxidative stress and testicular hormones, as previously described [64]. However, these findings are not consistent with those of another study [37], which suggested that Leydig cell damage leads to decreased testosterone levels, triggering an increase in LH and FSH to compensate for the testosterone shortfall. The discrepancy between results could be due to variations in the dosage and duration of CP exposure.

The present data indicate that CP triggers apoptosis and cell death by increasing ROS and compromising the total antioxidant capacity of the mitochondria. This leads to a disruption in mitochondrial redox processes and the induction of caspase-3ŌĆōassociated apoptosis [65,66]. These findings align with those of previous research [67]. The apoptotic effect of CP may be attributed to the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, which is initiated by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins. This accumulation can result from ionized calcium leakage, protein overload, oxidative stress, iron imbalance, or hypoxia. Subsequently, the unfolded protein response is activated through three signaling pathways originating from endoplasmic reticulum stress sensors, culminating in the induction of apoptosis [9,68]. CP initially activates p53, which then leads to the activation of Bax and Bak. This activation results in the release of cytochrome c through the mitochondrial membrane, followed by the activation of a cascade of caspases. These caspases play a pivotal role in apoptosis by hydrolyzing cytoskeletal and nuclear proteins, which include proteins involved in cell division, DNA repair, replication, and transcription. Additionally, Bax functions as an inhibitor of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [69-71].

Previous research has established a positive correlation between oxidative stress and apoptosis [72]. Specifically, the excessive production of ROS leads to an increase in apoptotic markers. Conversely, the oral administration of bilberry, both prior to and concurrently with CP, exerts an opposing effect on apoptosis relative to CP alone. This is attributed to bilberryŌĆÖs antioxidant properties and capacity to scavenge free radicals, which results in a reduction of oxidative stress. Consequently, apoptosis is diminished due to the upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and the downregulation of pro-apoptotic proteins such as caspase 3 [47].

In the present study, the tail DNA percentage, length, and moment were found to be significantly increased in the CP group compared to the control animals. This can be attributed to several factors. First, the overproduction of ROS is a primary cause of DNA fragmentation and base changes [73,74]. Second, the mechanism of apoptosis is triggered by the interaction of CP with DNA molecules, leading to the formation of DNA adducts [75]. These findings are consistent with the observed positive correlation between oxidative stress and tail moment. The Comet assay revealed comparatively good outcomes in the group treated with bilberry, as it contains anthocyanins that exert a genoprotective effect and shield DNA from the oxidative damage induced by CP [76].

In conclusion, the present findings, along with those from previous research, demonstrate that CP induces testicular toxicity and results in severe damage to the testicular architecture. Additionally, this study suggests that bilberry serves as an effective protective agent against testicular disorders and the oxidative stress associated with CP exposure. This protective effect may be due to bilberryŌĆÖs capacity to scavenge the free radicals responsible for causing testicular damage. Consequently, it is advisable for individuals exposed to CP to use bilberry as a dietary supplement to safeguard against the detrimental effects of CP on fertility.

Figure┬Ā1.

Microphotographs illustrating morphologically normal sperm and various sperm defects (original magnification ├Ś200). (A) Normal morphology. (B, D). Irregular head. (C, D) Tailless head. (E) Coiled tail. (F) Double tail.

Figure┬Ā2.

Photographic plate for DNA damage (├Ś200). The genotoxic potential of cisplatin (CP) in sperm of treated rats using the comet assay as highly effective tool for the biomonitoring of DNA integrity was assessed; control (A) and bilberry groups (B) showed normal undamaged DNA where cells appeared as compact head without any DNA damage. (C) CP and (D) bilberry+CP groups showed increased DNA damage; where cells with fragmented DNA appeared as a distinct head with a tail compared with control group. Administration of bilberry with CP (D) showed lesser DNA damage compared with CP group (C).

Figure┬Ā3.

(A) Control group showed normal seminiferous tubules with normal spermatogenesis. (B) Bilberry group showed normal seminiferous tubules and normal structure (similar to control group). (C) Cisplatin (CP) group showed seminiferous tubules with degenerated spermatids with arrest of spermatogenesis at 2nd spermatids. (D) Bilberry+CP showed mild improvement of seminiferous tubules with some of them restored normal spermatogenesis. The magnification is ├Ś200.

Figure┬Ā4.

Correlations between various parameters. MDA, malondialdehyde; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

Table┬Ā1.

Testis weight and testis weight/body weight ratio in the four groups

Table┬Ā2.

Effects of cisplatin and bilberry treatment on enzymatic antioxidants and markers of oxidative stress

Values are presented as mean┬▒standard error of 10 animals.

CP, cisplatin; MDA, malondialdehyde; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; GSH, glutathione; GST, glutathione S-transferase.

a)Significant difference from the control group at pŌēż0.05; b)Significant difference from the CP group at pŌēż0.05.

Table┬Ā3.

Effects of cisplatin and bilberry treatment on sperm count, motility, viability, and morphology

Table┬Ā4.

Effects of cisplatin and bilberry treatment on male reproductive hormone levels

Table┬Ā5.

Effects of CP and bilberry treatment on apoptosis

Table┬Ā6.

Effects of cisplatin and bilberry treatment on DNA damage in rat sperm

References

1. Wheate NJ, Walker S, Craig GE, Oun R. The status of platinum anticancer drugs in the clinic and in clinical trials. Dalton Trans 2010;39:8113-27.

2. Benedetti G, Fredriksson L, Herpers B, Meerman J, van de Water B, de Graauw M. TNF-╬▒-mediated NF-╬║B survival signaling impairment by cisplatin enhances JNK activation allowing synergistic apoptosis of renal proximal tubular cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2013;85:274-86.

3. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;740:364-78.

4. Peres LA, da Cunha AD Jr. Acute nephrotoxicity of cisplatin: molecular mechanisms. J Bras Nefrol 2013;35:332-40.

5. Trbojevic I, Ognjanovic B, Dordevic N, Markovic S, Stajn A, Gavric J, et al. Effects of cisplatin on lipid peroxidation and the glutathione redox status in the liver of male rats: the protective role of selenium. Arch Biol Sci 2010;62:75-82.

6. Afsar T, Razak S, Khan MR, Almajwal A. Acacia hydaspica ethyl acetate extract protects against cisplatin-induced DNA damage, oxidative stress and testicular injuries in adult male rats. BMC Cancer 2017;17:883.

7. Chirino YI, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Role of oxidative and nitrosative stress in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2009;61:223-42.

8. Pandir D, Kara O. Chemopreventive effect of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) against cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage as shown by the comet assay in peripheral blood of rats. Biologia 2014;69:811-6.

9. Soni KK, Kim HK, Choi BR, Karna KK, You JH, Cha JS, et al. Dose-dependent effects of cisplatin on the severity of testicular injury in Sprague Dawley rats: reactive oxygen species and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016;10:3959-68.

10. Tousson E, Hafez E, Masoud A, Hassan AA. Abrogation by curcumin on testicular toxicity induced by cisplatin in rats. J Cancer Res Treat 2014;2:64-8.

11. Ali BH, Al Moundhri MS. Agents ameliorating or augmenting the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin and other platinum compounds: a review of some recent research. Food Chem Toxicol 2006;44:1173-83.

12. He L, He T, Farrar S, Ji L, Liu T, Ma X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;44:532-53.

13. Chen W, Jia Z, Pan MH, Anandh Babu PV. Natural products for the prevention of oxidative stress-related diseases: mechanisms and strategies. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016;2016:4628502.

14. Upton R. Bilberry fruit: Vaccinium myrtillus L.: standards of analysis, quality control, and therapeutics. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia; 2001.

15. Erlund I, Koli R, Alfthan G, Marniemi J, Puukka P, Mustonen P, et al. Favorable effects of berry consumption on platelet function, blood pressure, and HDL cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:323-31.

16. Zafra-Stone S, Yasmin T, Bagchi M, Chatterjee A, Vinson JA, Bagchi D. Berry anthocyanins as novel antioxidants in human health and disease prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res 2007;51:675-83.

17. Ashour OM, Elberry AA, Alahdal A, Al Mohamadi AM, Nagy AA, Abdel-Naim AB, et al. Protective effect of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) against doxorubicin-induced oxidative cardiotoxicity in rats. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:BR110-5.

18. Pandir D, Kara O, Kara M. Protective effect of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) on cisplatin induced ovarian damage in rat. Cytotechnology 2014;66:677-85.

19. Seed J, Chapin RE, Clegg ED, Dostal LA, Foote RH, Hurtt ME, et al. Methods for assessing sperm motility, morphology, and counts in the rat, rabbit, and dog: a consensus report. ILSI Risk Science Institute Expert Working Group on Sperm Evaluation. Reprod Toxicol 1996;10:237-44.

20. Ciftci O, Ozdemir I, Aydin M, Beytur A. Beneficial effects of chrysin on the reproductive system of adult male rats. Andrologia 2012;44:181-6.

21. Stocks J, Dormandy TL. The autoxidation of human red cell lipids induced by hydrogen peroxide. Br J Haematol 1971;20:95-111.

22. Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med 1963;61:882-8.

24. DeChatelet LR, McCall CE, McPhail LC, Johnston RB Jr. Superoxide dismutase activity in leukocytes. J Clin Invest 1974;53:1197-201.

25. Bajpayee M, Dhawan A, Parmar D, Pandey AK, Mathur N, Seth PK. Gender-related differences in basal DNA damage in lymphocytes of a healthy Indian population using the alkaline Comet assay. Mutat Res 2002;520:83-91.

26. Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 6th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. p. 135-60.

27. Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS. Statistical methods in medical research. 4th ed. Wiley; 2001. p. 760-83.

28. Sylla BS, Wild CP. A million Africans a year dying from cancer by 2030: what can cancer research and control offer to the continent? Int J Cancer 2012;130:245-50.

29. Lu QB, Zhang QR, Ou N, Wang CR, Warrington J. In vitro and in vivo studies of non-platinum-based halogenated compounds as potent antitumor agents for natural targeted chemotherapy of cancers. EBioMedicine 2015;2:544-53.

30. Soni KK, Zhang LT, You JH, Lee SW, Kim CY, Cui WS, et al. The effects of MOTILIPERM on cisplatin induced testicular toxicity in Sprague-Dawley rats. Cancer Cell Int 2015;15:121.

31. Burdulis D, Sarkinas A, Jasutiene I, Stackevicene E, Nikolajevas L, Janulis V. Comparative study of anthocyanin composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) and blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) fruits. Acta Pol Pharm 2009;66:399-408.

32. Neamtu AA, Szoke-Kovacs R, Mihok E, Georgescu C, Turcus V, Olah NK, et al. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extracts comparative analysis regarding their phytonutrient profiles, antioxidant capacity along with the in vivo rescue effects tested on a Drosophila melanogaster high-sugar diet model. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:1067.

33. Benzie IF, Wachtel-Galor S. Vegetarian diets and public health: biomarker and redox connections. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010;13:1575-91.

34. Yuce A, Atessahin A, Ceribasi AO, Aksakal M. Ellagic acid prevents cisplatin-induced oxidative stress in liver and heart tissue of rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2007;101:345-9.

35. Thireau J, Poisson D, Zhang BL, Gillet L, Le Pecheur M, Andres C, et al. Increased heart rate variability in mice overexpressing the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med 2008;45:396-403.

36. Anand H, Misro MM, Sharma SB, Prakash S. Protective effects of Eugenia jambolana extract versus N-acetyl cysteine against cisplatin-induced damage in rat testis. Andrologia 2015;47:194-208.

37. Dare A, Olaniyan OT, Salihu MA, Illesanmi KL. L-ergothioneine supplement protect testicular functions in cisplatin-treated Wistar rats. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci 2019;14:6-13.

38. Elsayed A, Elkomy A, Alkafafy M, Elkammar R, El-Shafey A, Soliman A, et al. Testicular toxicity of cisplatin in rats: ameliorative effect of lycopene and N-acetylcysteine. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022;29:24077-84.

39. Chandra AK, Chatterjee A, Ghosh R, Sarkar M. Vitamin E-supplementation protect chromium (VI)-induced spermatogenic and steroidogenic disorders in testicular tissues of rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2010;48:972-9.

40. Kurt N, Turkeri ON, Suleyman B, Bakan N. The effect of taxifolin on high-dose-cisplatin-induced oxidative liver injury in rats. Adv Clin Exp Med 2021;30:1025-30.

41. Silici S, Ekmekcioglu O, Eraslan G, Demirtas A. Antioxidative effect of royal jelly in cisplatin-induced testes damage. Urology 2009;74:545-51.

42. Saad AA, Youssef MI, El-Shennawy LK. Cisplatin induced damage in kidney genomic DNA and nephrotoxicity in male rats: the protective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract. Food Chem Toxicol 2009;47:1499-506.

43. Reedijk J. Platinum anticancer coordination compounds: study of DNA binding inspires new drug design. Eur J Inorg Chem 2009;2009:1303-12.

44. Asadi N, Bahmani M, Kheradmand A, Rafieian-Kopaei M. The impact of oxidative stress on testicular function and the role of antioxidants in improving it: a review. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11:IE01-5.

45. Turk G, Atessahin A, Sonmez M, Ceribasi AO, Yuce A. Improvement of cisplatin-induced injuries to sperm quality, the oxidant-antioxidant system, and the histologic structure of the rat testis by ellagic acid. Fertil Steril 2008;89(5 Suppl): 1474-81.

46. Beytur A, Ciftci O, Oguz F, Oguzturk H, Yilmaz F. Montelukast attenuates side effects of cisplatin including testicular, spermatological, and hormonal damage in male rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:207-13.

47. Wang Y, Zhao L, Lu F, Yang X, Deng Q, Ji B, et al. Retinoprotective effects of bilberry anthocyanins via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic mechanisms in a visible light-induced retinal degeneration model in pigmented rabbits. Molecules 2015;20:22395-410.

48. Bao L, Yao XS, Yau CC, Tsi D, Chia CS, Nagai H, et al. Protective effects of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract on restraint stress-induced liver damage in mice. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:7803-7.

49. Mesbahzadeh B, Hassanzadeh-Taheri M, Aliparast MS, Baniasadi P, Hosseini M. The protective effect of crocin on cisplatin-induced testicular impairment in rats. BMC Urol 2021;21:117.

50. Rauf N, Nawaz A, Ullah H, Ullah R, Nabi G, Ullah A, et al. Therapeutic effects of chitosan-embedded vitamin C, E nanoparticles against cisplatin-induced gametogenic and androgenic toxicity in adult male rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021;28:56319-32.

51. Ilbey YO, Ozbek E, Cekmen M, Simsek A, Otunctemur A, Somay A. Protective effect of curcumin in cisplatin-induced oxidative injury in rat testis: mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathways. Hum Reprod 2009;24:1717-25.

52. Almeer RS, Abdel Moneim AE. Evaluation of the protective effect of olive leaf extract on cisplatin-induced testicular damage in rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018;2018:8487248.

53. Eid AH, Abdelkader NF, Abd El-Raouf OM, Fawzy HM, ElSayeh BM, El-Denshary ES. Protective effect of L-carnitine against cisplatin-induced testicular toxicity in rats. Al-Azhar J Pharm Sci 2016;53:123-42.

54. Amin A, Abraham C, Hamza AA, Abdalla ZA, Al-Shamsi SB, Harethi SS, et al. A standardized extract of Ginkgo biloba neutralizes cisplatin-mediated reproductive toxicity in rats. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012;2012:362049.

55. Fulco BC, Jung JT, Brum LO, Zborowski VA, Goulart TA, Nogueira CW. Similar hepatoprotective effectiveness of Diphenyl diselenide and Ebselen against cisplatin-induced disruption of metabolic homeostasis and redox balance in juvenile rats. Chem Biol Interact 2020;330:109234.

56. El-Gany A, Nagib RM, Bakry N, Bakry S. Amelioration of cisplatin induced testicular injury by different garlic preparations in experimental rat world. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 2016;5:160-81.

57. Hamam ET, Awadalla A, Shokeir AA, Aboul-Naga AM. Zinc oxide nanoparticles attenuate prepubertal exposure to cisplatin-induced testicular toxicity and spermatogenesis impairment in rats. Toxicology 2022;468:153102.

58. Tumbas V, Canadanovic-Brunet J, Gille L, Dilas S, Cetkovic G. Superoxide anion radical scavenging activity of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.). J Berry Res 2010;1:13-23.

59. Phan TT, Wang L, See P, Grayer RJ, Chan SY, Lee ST. Phenolic compounds of Chromolaena odorata protect cultured skin cells from oxidative damage: implication for cutaneous wound healing. Biol Pharm Bull 2001;24:1373-9.

60. Tsuda T, Ueno Y, Kojo H, Yoshikawa T, Osawa T. Gene expression profile of isolated rat adipocytes treated with anthocyanins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005;1733:137-47.

61. Fallahzadeh AR, Rezaei Z, Rahimi HR, Barmak MJ, Sadeghi H, Mehrabi S, et al. Evaluation of the effect of pentoxifylline on cisplatin-induced testicular toxicity in rats. Toxicol Res 2017;33:255-63.

62. Atessahin A, Karahan I, Turk G, Gur S, Yilmaz S, Ceribasi AO. Protective role of lycopene on cisplatin-induced changes in sperm characteristics, testicular damage and oxidative stress in rats. Reprod Toxicol 2006;21:42-7.

63. Hozayen WG. Effect of hesperidin and rutin on doxorubicin induced testicular toxicity in male rats. Int J Food Nutr Sci 2012;1:31-42.

64. Darbandi M, Darbandi S, Agarwal A, Sengupta P, Durairajanayagam D, Henkel R, et al. Reactive oxygen species and male reproductive hormones. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018;16:87.

65. Meng H, Fu G, Shen J, Shen K, Xu Z, Wang Y, et al. Ameliorative effect of daidzein on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice via modulation of inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:3140680.

66. Liu HT, Wang TE, Hsu YT, Chou CC, Huang KH, Hsu CC, et al. Nanoparticulated honokiol mitigates cisplatin-induced chronic kidney injury by maintaining mitochondria antioxidant capacity and reducing caspase 3-associated cellular apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019;8:466.

67. Alt─▒ndag F, Meydan I. Evaluation of protective effects of gallic acid on cisplatin-induced testicular and epididymal damage. Andrologia 2021;53:e14189.

68. Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem 2005;74:739-89.

69. Gonzalez VM, Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Perez JM. Is cisplatin-induced cell death always produced by apoptosis? Mol Pharmacol 2001;59:657-63.

70. Rastogi RP, Sinha RP. Apoptosis: molecular mechanisms and pathogenicity. EXCLI J 2019;8:155-181.

71. Tanida S, Mizoshita T, Ozeki K, Tsukamoto H, Kamiya T, Kataoka H, et al. Mechanisms of cisplatin-induced apoptosis and of cisplatin sensitivity: potential of BIN1 to act as a potent predictor of cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer treatment. Int J Surg Oncol 2012;2012:862879.

72. Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1863:2977-92.

73. Sakkas D, Seli E, Manicardi GC, Nijs M, Ombelet W, Bizzaro D. The presence of abnormal spermatozoa in the ejaculate: did apoptosis fail? Hum Fertil (Camb) 2004;7:99-103.

74. Evenson DP, Wixon R. Clinical aspects of sperm DNA fragmentation detection and male infertility. Theriogenology 2006;65:979-91.